Unearthing the Desert of Maine: A Hidden History in the Pine Tree State

Share

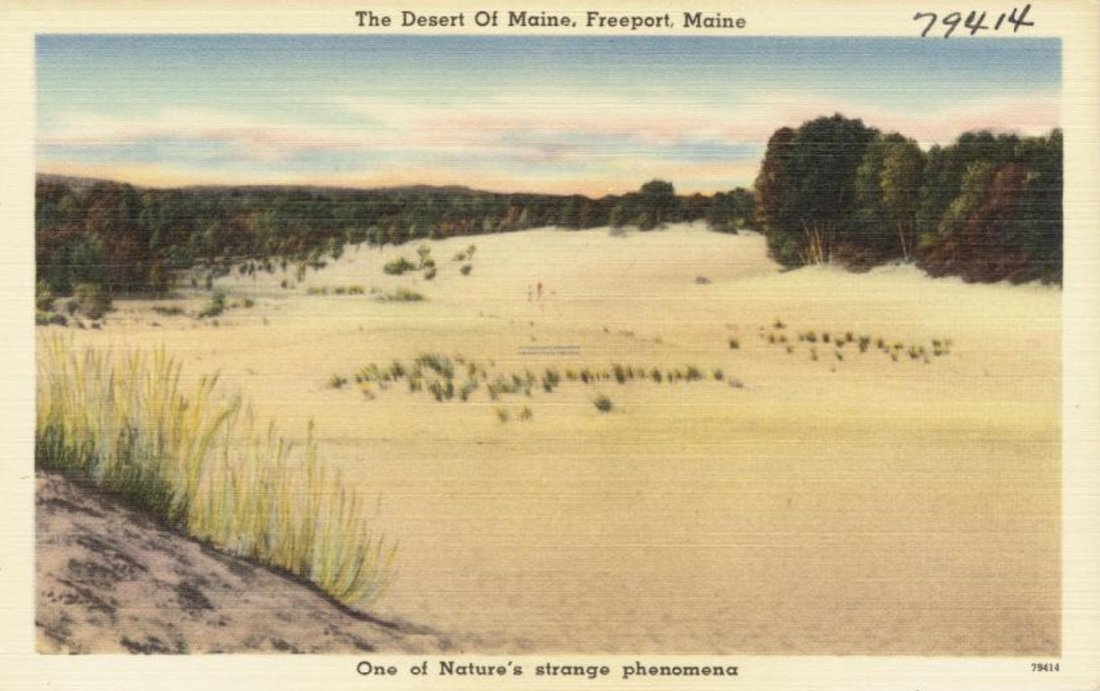

When you think of Maine, what comes to mind? Towering pines, jagged coastlines, lobster rolls, and maybe a moose or two? You’d be forgiven for not picturing a desert—after all, this is New England, not Nevada. But tucked away near the bustling outlet town of Freeport lies one of Maine’s strangest secrets: the Desert of Maine. Spanning 40 acres of shifting sands amidst a sea of green forest, this anomaly isn’t just a quirky roadside stop—it’s a window into a fascinating history of geology, human missteps, and entrepreneurial spirit. Let’s dig into the story of how a patch of farmland turned into a miniature Sahara.

A Glacial Gift from Millennia Past

The Desert of Maine’s tale begins long before humans set foot on the land—about 15,000 years ago, to be exact. During the last Ice Age, the Laurentide Ice Sheet blanketed New England, grinding rocks into fine silt as it crept across the landscape. As the glaciers retreated, they left behind deposits of this glacial sand in what’s now Freeport. For thousands of years, a thin layer of topsoil capped this sandy underbelly, supporting lush vegetation and hiding the desert-to-be. It was a sleeper agent of nature, waiting for the right moment to reveal itself.

Fast forward to the late 1700s, when European settlers began trickling into Maine. Among them was William Tuttle, who in 1797 bought a 300-acre plot near Freeport. He and his family hauled their house and barn from Portland with oxen, setting up a thriving farm. Potatoes grew in the fields, cattle grazed the pastures, and later, the Tuttles added sheep to cash in on the wool trade. It was a picture of rural success—until it wasn’t.

The Sands of Misfortune

Here’s where human error enters the stage. The Tuttles, like many farmers of their time, didn’t practice crop rotation, a technique that keeps soil healthy by alternating what’s planted. Instead, they kept hammering the land with potatoes and grazing sheep, which munched the grass down to its roots. By the mid-1800s, the soil was exhausted. Overgrazing and poor farming stripped away that precious topsoil cap, exposing the glacial silt beneath. What started as small sandy patches grew into sprawling dunes as wind whipped the loose silt into heaps. The farm became a barren wasteland, swallowing fields, trees, and even parts of the homestead. By 1890, the Tuttles threw in the towel and abandoned their sandy nightmare.

For a while, the land sat as a local curiosity, dubbed "the sand farm." But its transformation into the Desert of Maine as we know it today came thanks to a man with a vision—and a knack for turning lemons into lemonade.

From Ruin to Roadside Wonder

Enter Henry Goldrup, an entrepreneur with an eye for opportunity. In 1925, he bought the desolate 300-acre plot for a mere $300 (about $5,200 in today’s money). Goldrup saw potential where others saw failure. He christened it the "Desert of Maine" and opened it as a tourist attraction, capitalizing on its bizarre contrast to Maine’s greenery. At first, he didn’t even charge admission—just sold hot dogs and ice cream to curious passersby. But the crowds grew, and soon he was offering tours, complete with a Model T Ford for photo ops and even a live camel named Sarah (who, legend has it, wasn’t thrilled about her gig and took to spitting at tourists).

Goldrup’s venture was a hit. By the 1930s, the Desert of Maine was a must-see stop along Route 1, complete with postcards and a reputation as one of Maine’s earliest roadside attractions. Over the decades, it evolved—adding a barn museum with antique tools, a spring house (later buried under 25 feet of sand during World War II), and even fruit trees that somehow still bore cherries despite being half-submerged.

A Shrinking Marvel in Modern Times

Today, the Desert of Maine is smaller than it once was. What spanned over 100 acres at its peak has shrunk to about 20-25 acres as pine trees and hardy brush reclaim the edges. The same winds that built the dunes are now blowing the sand south into a creek, slowly washing it away. Yet its core remains a rugged, surreal landscape that defies its surroundings.

Since 2018, new owners Mela Jones and her partner have breathed fresh life into the site. They’ve added a mini-golf course, a campground with glamping tents, and plans for an arts center in the restored Tuttle barn. The spring house, excavated in 2021, is being rebuilt, and an 1800s-style train now chugs visitors around the dunes. It’s a blend of history and whimsy, drawing families, geology buffs, and adventurers alike.

A Lesson in Sand and Resilience

The Desert of Maine isn’t a true desert—southern Maine gets too much rain for that—but its story is a testament to nature’s power and humanity’s role in shaping it. It’s a reminder of what happens when we push the land too hard, and how creativity can turn a disaster into a legacy.